Investing in India? Look Beyond Modi’s Economic Policies

In light of the upcoming general elections, India Briefing assesses the outcomes of the Modi government’s major economic goals in the last five years, and discusses why businesses need to look beyond Modi when choosing to invest in India.

In 2014, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi established a government, businesses rejoiced, markets soared, and foreign investors poured billions of dollars into Indian stocks. Modi, in his election campaign, had promised millions of jobs and a large economic reform agenda.

Now, at the end of his five-year tenure, Modi is yet to deliver on most of these promises. However, the Indian economy has continued to grow at an average rate of 7.6 percent, mostly led by an increase in consumption.

Political leaders and their policies play a big role in shaping India’s business environment. But these factors should not alone impact your investment strategy for the country.

In this article, we assess the outcomes of the Modi government’s major economic goals, and discuss why businesses need to look beyond Modi when choosing to invest in India.

Growth

India is one of the fastest growing economies in the world. It outpaced China’s growth rate in 2014, and replaced France as the sixth largest economy in the world in 2018.

With investments picking up, and consumption remaining strong, global institutes estimate India’s gross domestic product (GDP) to average 7.5 percent in 2019 and 2020.

However, for the fiscal year 2018-19, the revised estimates by the government show a decline in the GDP rate from 7.2 percent to 7 percent. This is the lowest pace of growth in five years and nearly the same as the year before Modi took over.

The high economic growth achieved in the initial years of the Modi government has also failed to translate into higher incomes or new jobs.

Many analysts assert that India’s growth is not meeting the country’s needs: either current growth needs to become more inclusive or growth needs to start to outperform current rates.

Employment

During the 2014 election campaign, Modi promised to create 10 million jobs annually to eliminate unemployment. Contrary to expectations, the five years under Modi have seen a record decline in new jobs created.

Several industry reports (by Oxfam, McKinsey) and leaked data from the statistics ministry (the government claims that the unemployment report 2017-18 is a draft) highlight a jobs crisis and rising unemployment.

Unemployment was at 7.4 percent in December 2018 – the highest in more than two years, according to a Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) report.

The unemployment situation for women is even worse. In 2018, about 8.8 million Indian women lost their jobs in comparison to only 2.2 million men. The World Bank reports that only 27 percent of women in India participate in the workforce – one of the lowest rates in South Asia.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates the number of unemployed Indians will rise to 18.9 million in 2019, from 18.6 million in 2018 and 18.3 million in 2017.

The rise in joblessness is partly a result of the botched attempt to demonetize currency in 2016 and rushing into a poorly implemented goods and services tax (GST) system in 2017. Both reforms adversely affected sectors – like construction, agriculture, and textiles – that harbor a large share of unorganized labor, which still accounts for the vast majority of the workforce.

With 5 to 7 million youths entering the labor market ever year, India can ill-afford sub-par job creation performance and the current trajectory of unemployment.

Investments

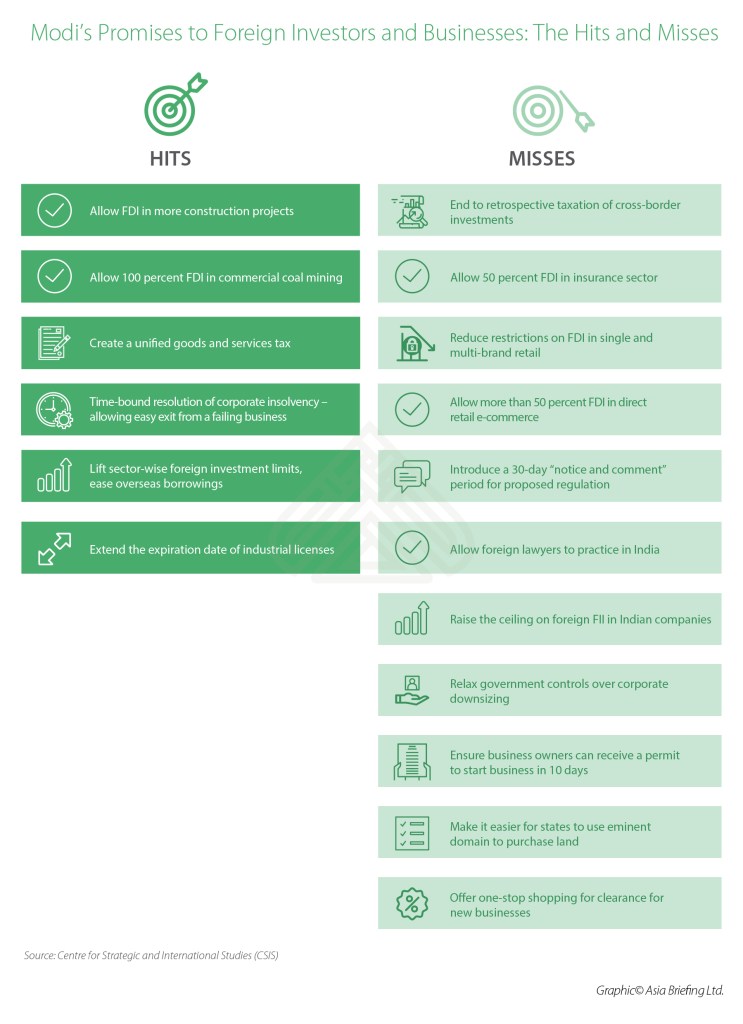

The Modi government accomplished a number of business reforms, such as opening new sectors for foreign investment, the GST to unify fragmented state markets, and the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) to ensure time-bound settlement of insolvency. However, a large part of the government’s reform agenda remains a work in progress.

Restrictive land and labor regulations, bureaucratic bottlenecks, a banking system dominated by state-owned banks, and poor infrastructure are some of the key reasons that have kept the investors away.

The latest data by CMIE shows that delays in clearances for environmental and non-environmental purposes, land acquisition problems, lack of funds for government projects, as well as unfavorable market conditions have stalled a number of projects since 2014.

In October-December 2018, the value of stalled projects shot up to INR 3.18 trillion (US$46.17 billion) while the number of new projects stood at their lowest level since 2014.

Though foreign direct investment (FDI) has increased in absolute numbers from US$45.15 billion in FY 2015 to US$60.97 billion in FY 2018, the rate of FDI growth has declined in the last two years.

It is important to note that the increase in FDI inflow is a result of investments made in acquiring existing businesses (such as the Flipkart acquisition by Walmart), and not setting up new ones.

Other factors that can explain the increase in FDI include delayed reporting, notional inflows, inappropriate industrial classifications, and round tripping. Round tripping occurs when money flows to a foreign country – such as Mauritius and Cyprus, which are two of the largest sources of FDI for India — serve as a foreign-exchange haven and comes back as FDI.

Modi identified foreign investment as a key driver for growing industry and creating jobs, but foreign investors simply have not responded to the government’s reforms as anticipated in 2014.

Manufacturing

More than four years after Modi launched his flagship program – Make in India – to boost investments in manufacturing, the scheme shows little sign of momentum.

The share of manufacturing in India’s overall GDP has come down from 17.4 percent in 2006 to 15 percent in 2017. This is far short of the program’s goal of bringing manufacturing’s share up to 25 percent by 2025.

In fact, last year, manufacturing did not feature within the top ten sectors for FDI into the country.

Despite numerous incentive schemes and pledges for reforms, the government has not shown the willingness to reform the outdated land and labor policies that often impede investments.

The occasional political interference and lack of support for small manufacturers are some of the other aspects that have led to the failure of the project.

India has more to offer than Modi’s economic reforms

Whether Modi failed to deliver on his many promises, or those promises did not create the intended effect, it is difficult to imagine the private sector responding to Modi’s re-election in 2019 in the same way as Modi’s election in 2014.

However, it is important for investors assessing government policies to recognize that businesses succeed in India not because of its government, but in spite of it.

India has one of the fastest growing service sectors in the world. Industries such as information technology, telecom, healthcare, tourism, education, and professional services – including audit and accounting, management consulting, architectural, and legal services – are globally competitive.

In 2018, the sector attracted the highest amount of FDI inflows and contributed significantly to exports; it accounts for about 60 percent of the country’s GDP.

India’s growth in consumer spending is more than double the anticipated global rate, and is likely to make it the third largest consumer market by 2030, behind only the US and China. The increase in consumer spending, and changes in consumer behavior and pattern represent massive opportunities that lie in the Indian market. Businesses that are interested in selling to a massive unified market in Asia will find a lot of opportunities when they examine India.

India has one of the lowest labor costs in Asia: its hourly labor cost is roughly one third of that in China. And with a population of over 1.35 billion people, India has one of the largest labor markets globally. More than half of its total population is under the age of 25 years, and two-thirds of it is less than 35 years of age. Businesses that can invest in robust recruitment and training programs can realize labor costs that are difficult to achieve in other parts of Asia.

India’s federal governing system means that the business environment is not uniform across the country. Each state has its own policies and business profile. Businesses can benefit from a state-based market strategy, instead of treating India as a uniform market.

While many people are examining Modi’s policy record, there are many reasons to remain optimistic about India’s economic potential.

About Us

India Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia and maintains offices in China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, and Russia.

Please contact india@dezshira.com or visit our website at www.dezshira.com.

- Previous Article Regionale Markteintrittsstrategien in Indien

- Next Article Universal Basic Income in India – the Policies that are Shaping the Debate