India can expand its share in global value chains (GVCs) if it simplifies its customs and trade procedures and engages its vast MSME sector with global lead firms. The country is well poised to grow its GVC engagement as it pursues mega infrastructure programs and prioritizes new free trade agreements. Moreover, India has several sectors with production capacity that can be scaled for export-focused output. We discuss key constraints, sector-wise opportunities, and policy recommendations in this article. Foreign investors and lead firms should consider India as a more viable destination as it develops a strong network of OEMs and incentivizes the expansion of indigenous industrial supply chains besides continuously upgrading its logistics and infrastructure build.

Global value chains (GVCs) refer to the range of production activities from design, manufacturing, marketing, and distribution, up to the sale to end-consumers, which are split among several firms across different countries. Countries engage in GVCs either by backward or forward linkages. Backward linkages are formed when a country imports foreign inputs to produce goods and services they export, while forward linkages are formed when a country exports domestic inputs to countries in charge of downstream production.

Increased participation in GVCs can lead to growth in the economy, higher productivity, job creation, and raise living standards. According to the World Bank, a one percent increase in GVC participation is estimated to boost per capita income levels by more than one percent – about twice as much as conventional trade.

However, this can only be achieved if countries align their development strategies in multiple areas, such as trade policy, logistics, investment facilitation, taxation, education, and skill development.

Current global trends

GVCs are currently undergoing transition, driven by several factors like the need for diversification due to the pandemic and ensuring supply chain security due to strategic reasons. This has opened significant opportunities for newer countries to step up in existing value chains and capture greater market share.

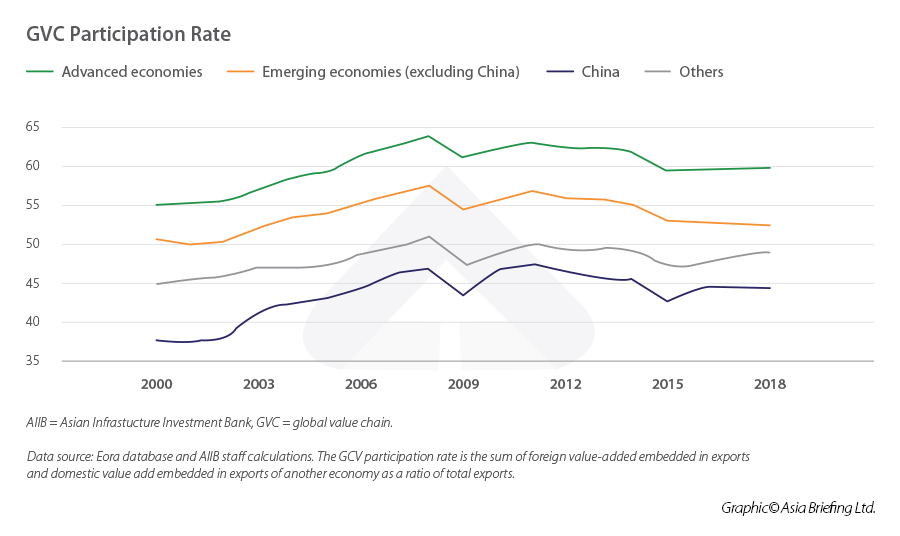

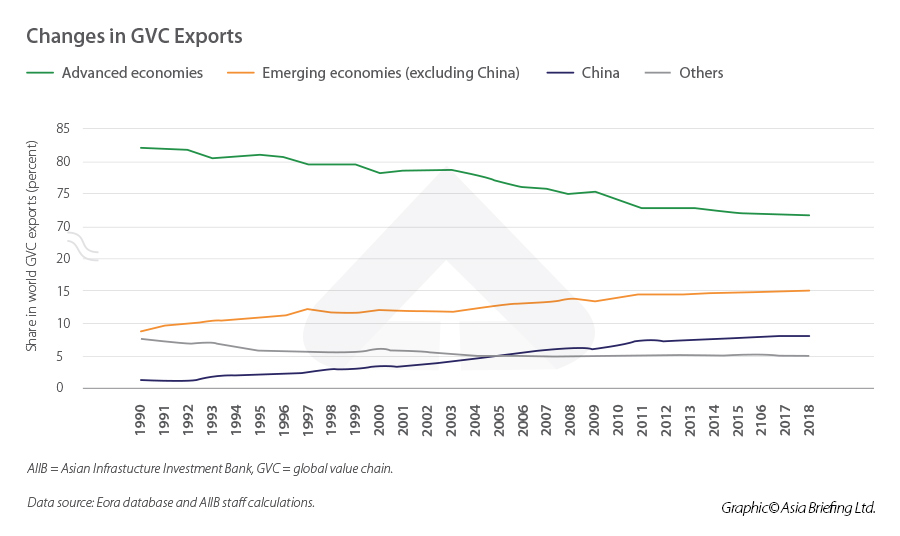

Between 2000 to 2018, the share of advanced economies in GVC exports, reduced from 78 percent to 72 percent, but it was still higher when compared to their share in the global GDP at 60 percent and exports at 64 percent. During the same period, the share of emerging economies in GVC exports increased from 14.6 percent to 21 percent, largely due to China, which increased its share from 3.6 percent to eight percent.

The shifting trend in GVCs will continue in the favor of emerging economies only if they overcome key challenges – increasing the number of lead firms, introducing more technology in their processes, easing business facilitation, and investing significantly in infrastructure.

Share in GVCs – comparison between major Asian economies

Below is a comparison of the different models of GVCs for prominent economies in Asia.

|

Country |

GVC position |

Productivity |

Innovation |

Role of foreign subsidiaries in trade |

Sourcing structure of foreign affiliates |

|

China |

Balanced |

Medium |

High |

High |

Domestic |

|

India |

Balanced |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Abroad |

|

Vietnam |

High backward linkages |

Low |

Low |

High |

Abroad but within the region |

|

South Korea |

High |

High |

Low |

Domestic |

|

|

Malaysia |

Medium |

Low |

High |

Abroad but within the region |

|

|

Thailand |

Low |

||||

|

Indonesia |

High(er) forward linkages |

Medium Low |

Low |

Medium |

Abroad |

Source: OECD, World Bank, WIPO

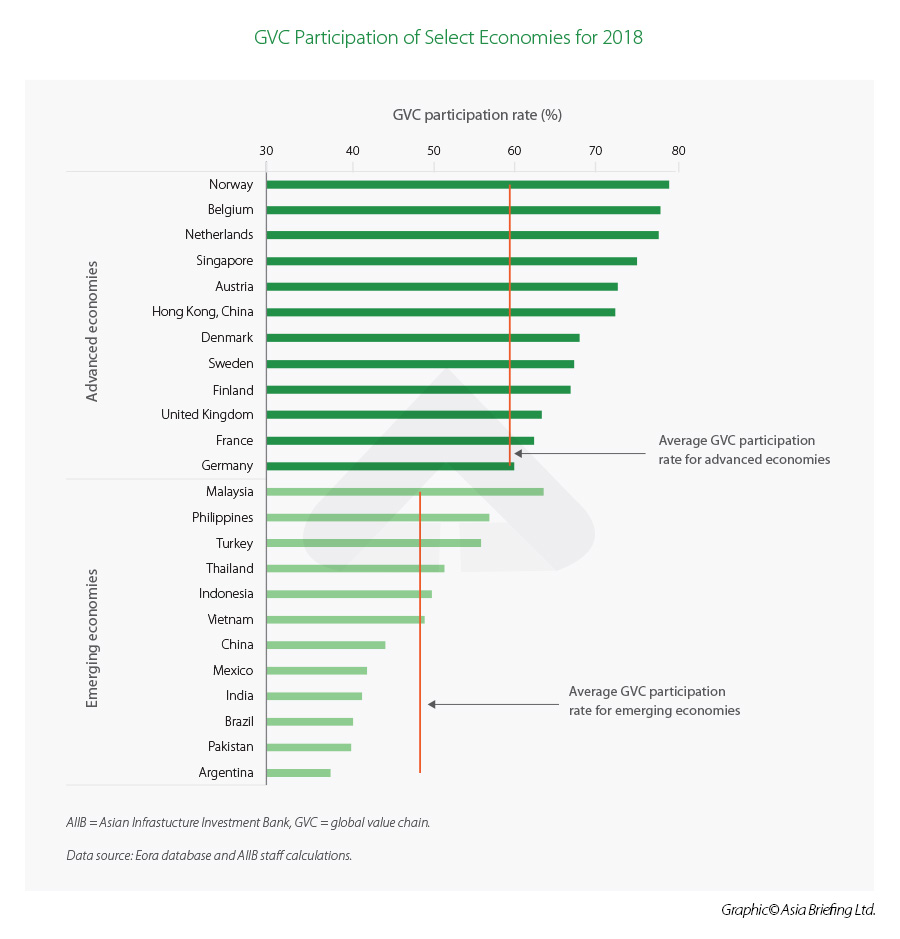

India's share in global value chains

India’s current share in GVC exports is significantly low not only when compared to large economies like the United States, China, and Japan, but also smaller countries like South Korea and Malaysia.

If India wants to capitalize on the ongoing GVC transition, it must take steps to take advantage of its huge consumer market, labor force, and implement investor-friendly government policies. If they do these successfully, India could redress its widening trade deficit and boost the job market, thereby leading to higher incomes.

India’s participation rate in GVC

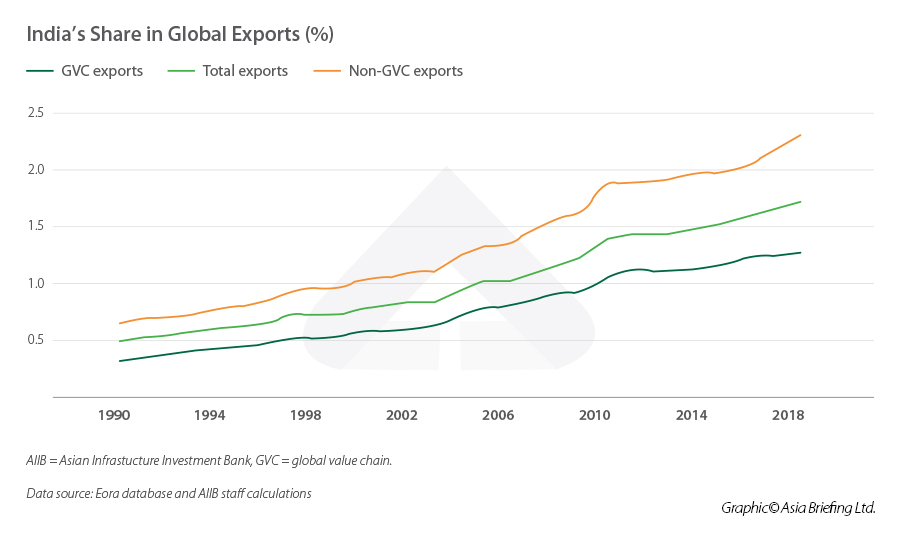

India’s share in global exports jumped from 0.5 percent in 1990 to 1.7 percent in 2018 to 2.1 percent in 2022. However, the share in GVCs did not witness proportionate growth. India’s GVC participation grew until 2008 to 47.6 percent but declined to 41.3 percent by 2018. GVC exports witnessed slower growth when compared to overall exports or non-GVC exports from 2008 to 2018.

India’s participation in GVC is mostly focused on forward linkages, rather than backward linkages. The country still depends heavily on exports of raw materials and intermediate products, rather than exports based on imported materials.

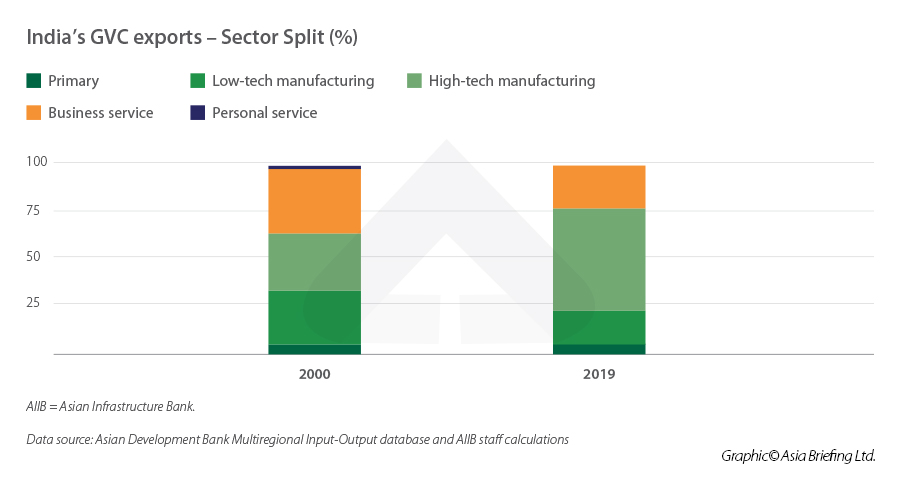

In the 2000s, high and low-tech manufacturing and business services had similar shares in GVC exports. By 2019, high-tech manufacturing had increased, accounting for more than half of the GVC exports.

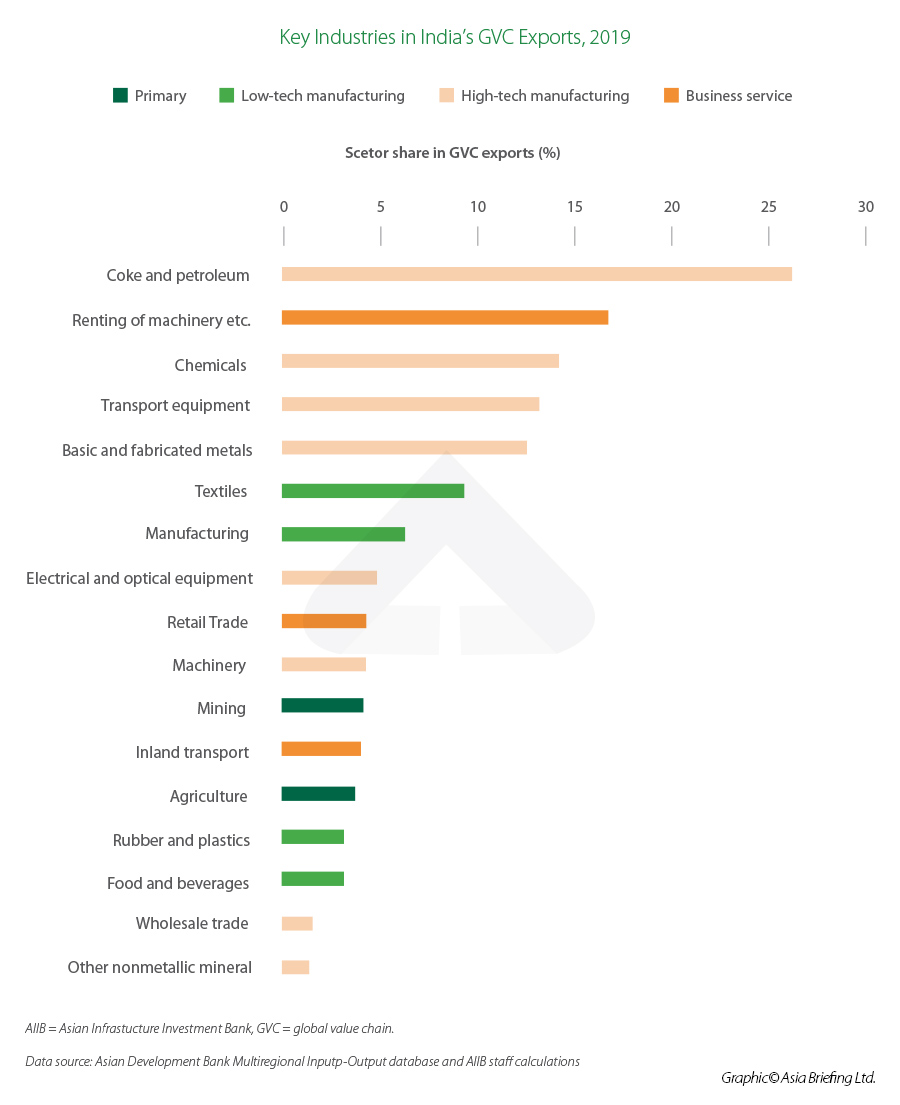

As for the share of industries, coke and petroleum led as of 2019, followed by renting of machinery and chemicals.

Uneven growth across Indian states

India has tried to strengthen its backward linkages since the 2000s by prioritizing high-tech exports, though this has largely concentrated in a few coastal states. The reasons are they possess larger air cargo facilities, inland depots, multimodal logistics hubs, better road networks, larger warehouse capacity, and port access, which make these states more competitive compared to the rest of India. However, studies show that investments in infrastructure in inland areas could lead to higher GVC participation. The Indian government is prioritizing the capture of this potential through various plans focused on advancing the logistics and infrastructure sectors and increasing capex on such projects.

In India, the central government is a key player in policy formulation for improving the country’s exports, but the individual state governments play an almost equal role as they are responsible for land, labor, utility, and skill development. Only six states in India – Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh – contribute to 70 percent of India’s overall exports.

In addition, these six states host more firms with foreign ownership, which leads to higher exports. Investors tend to prefer these states due to their well-defined industrial policies and good governance.

Other Indian states have tried to improve their attractiveness to foreign investors by improving their business environment or increasing engagement in key sectors but have lagged when it comes to infrastructure and power supply. After all, any business or manufacturing setup will calculate their operating costs as impacted by prevailing industrial infrastructure, access to logistics hubs, land availability and acquisition policy, and provision of efficient power supply.

Sector-wise opportunities for India's GVC engagement

India has not been able to capitalize fully on the opportunities offered by the shift in GVCs and attract lead firms largely due to its inward-looking measures – focus on protecting domestic industries through tariffs, subsidies, quotas, and other such measures. This policy default is now changing and has picked up pace since the pandemic through the roll-out of new production-oriented investment schemes and speeding up of mega infrastructure development. Geographically, India has huge advantages as a production and supply hub due to its access to vital trade routes, connecting the Far East and Southeast Asia with Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, huge consumer demand, proximity to major manufacturing hubs in Asia, and a growing working population. However, more needs to be done.

India can also take advantage of its large number of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to increase linkages with lead firms to enhance exports. For example, Vietnam is working closely with foreign manufacturers, such as Samsung, and domestic suppliers to improve productivity, management capacity, and product supply capacity – to strengthen supply chain linkages of domestic firms. MSMEs in India contribute around 30 percent to GDP and nearly 50 percent to the country’s exports. But this has not translated to an increase in engagement with GVCs due to weak innovation, lack of access to finance, and inadequate linkages with lead firms.

Another key area that India needs to focus on is the simplification of customs procedures and improving the trade infrastructure. For certain sectors, it is more feasible to invest in a slightly less competitive country than India in terms of labor or land cost, rather than having long delays in ports due to capacity issues or demanding as well as unclear customs procedures.

Most of the sector opportunities that currently exist are in downstream activities, due to their low labor costs. As for high-tech sectors like electronics, semiconductors, and pharmaceutical GVCs, India should focus more on increasing the skill content of the existing processes, by engaging in design or R&D activities, to increase its share in GVCs. India has an edge in several sectors, but they have largely been driven by domestic demand, rather than export-focused growth. Still, these are the same sectors that can jumpstart the process of increasing engagement in global value chains. In the case of defense, aerospace, and electronics, import substitution will be key for strategic reasons in the near future as domestic capacity is being built up. Meanwhile, India has the potential to establish export hubs in the below sectors:

- Pharmaceuticals and medical devices

- India has strong manufacturing capabilities and a cost advantage (30–35 percent lower) over the US and Europe.

- Specialty chemicals

- The sector has strong R&D capabilities and a growing supplier base.

- Apparel and footwear

- Cost advantage due to the availability of cheap raw materials and lower wages.

- Gems and jewelry

- Significant skilled workforce, reduction in import duties (such as for lab-grown diamonds as well as cut and polished diamonds), and free trade agreement with the UAE, which is a major export market

- Food processing

- High level of agricultural production with a large livestock base, wide variety of crops, inland water bodies and a long coastline, that can help increase marine production. In addition, government initiatives in the areas of cold chain infrastructure and quality assurance measures will be a driving factor.

- Auto and auto components (including electric vehicles)

- Strong supplier base (tier 2 and 3 cities), narrowing China-India cost differential, and increased presence of Indian original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) in markets such as Africa and Latin America.

Challenges

According to a 2022 survey by the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) of 200 domestic and foreign companies in India across six sectors – aerospace and defense, automotive and auto-components, capital goods, electronic systems design and manufacturing (ESDM), new and renewable energy, and pharmaceuticals and medical devices – there are some key constraints to GVC integration in India.

- Inability to meet quality standards

- Poor institutional support

- Lack of information

- Poor market access

- Lack of access to capital

- Inadequate business networks

- High domestic tariffs

- Low production capacity

With regards to the importance of GVC integration, 87 percent of respondents replied that it is very important, 10 percent answered somewhat important, and three percent said it is not important.

The survey noted that the factor most influencing investment decisions in India were “global macroeconomic developments” for aerospace and defense, capital goods, electronic system design and manufacturing, and pharma and medical devices.

For automobile and auto components and new and renewable energy, the key considerations were “domestic policies” and “climate and energy transitions”.

The top five factors that are key to FDI decisions as per the ORF survey are:

- Availability of raw materials

- Skilled workforce

- Cost of Production

- Quality of infrastructure

- Taxation rules and policies

These factors can also be seen as additional challenges that India needs to keep addressing if it wants its FDI trends to move upwards.

Key recommendations to address the challenges include the following:

- Geopolitical developments will accelerate the shift in GVCs, and India needs to ensure its policies, schemes, and incentives focus on enabling ease of doing business, providing cost advantages, avoiding delays, and reducing bureaucratic entanglements.

- India needs to encourage the development of the research ecosystem in educational institutions by incentivizing partnerships between industries and educational institutions, facilitating partnerships between leading Indian and foreign education and research institutions, increasing R&D funding in key institutions, and introducing research-intensive education programs.

- Government must continue its spending towards the country’s infrastructure sector, including on roads, railways, and airports.

- Import procedures need to be streamlined and hidden trade barriers reduced.

- Trade agreements should continue to be prioritized to widen India's market access.

- Tax regulations and procedures must be uniformly implemented and not frequently amended. Further, these should align with trade policies to assist firms in scaling up production.

- In the area of intellectual property (IP), India needs to increase R&D funding of its departments, incentivize the private sector to undertake research activities, increase awareness of IP among domestic entities, introduce a framework for IP-backed financing, increase the capacity of enforcement agencies, fast-track applications, and provide faster resolutions to IP disputes.

The long view

India needs to continue investing in its physical infrastructure to maintain its cost competitiveness, increase productivity, and scale up production.

Rather than only focusing on reducing reliance on imported materials, India also needs to develop capacities, acquire new capabilities, upgrade existing ones, improve trade facilitation, and incorporate MSMEs to increase GVCs integration.

If executed efficiently, GVCs will be a significant contributor to India’s economic growth, employment, productivity, and income.